A Road Trip Through Time: Exploring Mayan Ruins in Mexico

Writer Kassondra Cloos decends the Oval Palace at Ek Balam archaeological site in the state of Yucatán, Mexico.

Story by Kassondra Cloos; photos by Michael Ciaglo

Kassondra is a freelance travel writer based in Mexico City. Michael is a freelance photographer based in Denver, Colorado.

Sites in Yucatán and Quintana Roo offer awe-inspiring history lessons.

As I look out at the trees surrounding the ancient Mayan city of Cobá, the sun begins to set and I can’t help but appreciate the scheduling error that brought me here at just the right time. I always say it’s not a good road trip until you’ve made a mistake, and that we did.

Failing to plan for the time zone change between the adjacent Mexican states of Yucatán and Quintana Roo, my friend Michael and I arrive at Cobá after regular tour hours. We agree to pay a special late admission fee, which buys us an unexpected advantage: so few tourists wander the massive complex that we have it — and the sunset — almost to ourselves.

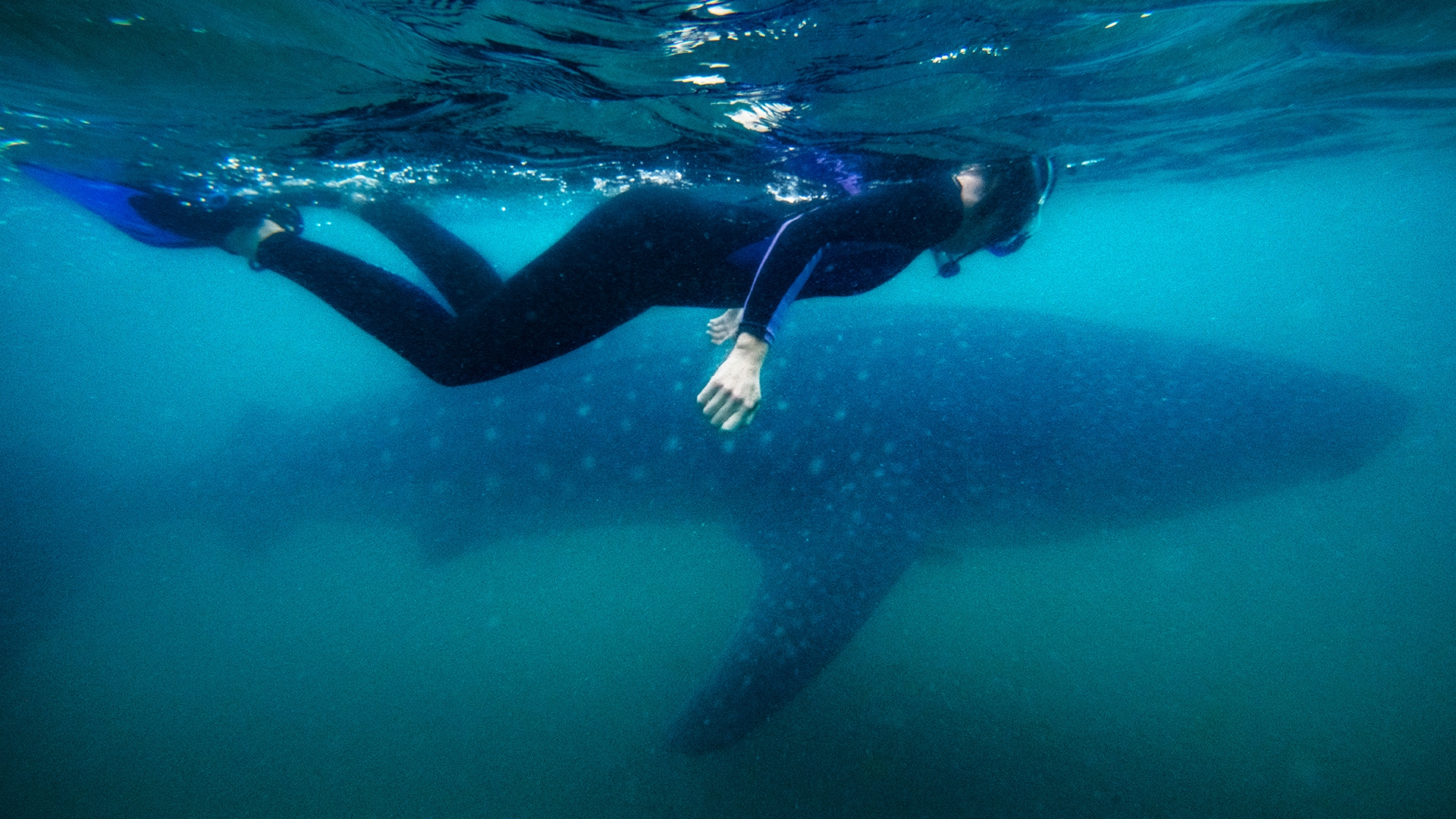

For five days, Michael and I make good use of our rental car, crisscrossing the state border as we travel between Quintana Roo — home of Cancun, Tulum and an overwhelming number of modern-day attractions — and the quieter, slower-paced state of Yucatán. In addition to time at the beach and swimming in crystal-clear cenotes (natural pits or sinkholes), we intend to visit the ruins of five of the ancient cities built by the Mayans.

Kassondra climbs the Nohoch Mul pyramid at Cobá, an ancient Mayan city.

A chef grills chicken and pineapple at Pollos Los Pajaros in Pisté in Yucatán.

Our first morning in Cancun, we park in a seaside lot in the heart of the hotel district, where tourists by the dozens pose for photos with a colorful sculpture of the city’s name. We pass on that opportunity and cross the street, where we wander through the ruins of the ancient port city, El Rey, once part of an important trade route. Today, large iguanas sunning themselves on the stone ruins outnumber visitors 10, or even 20, to 1. Eighty-one miles south of Cancun, the ruins at Tulum also overlook the sea, and there we wonder whether the Mayans who lived here in the 13th century prized their ocean views.

A visit to Chichén Itzá, in the state of Yucatán, requires some planning. The crown jewel of Mexico’s archaeological sites, the famous ruins are about a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Cancun on Highway 180. The night before our visit, we head for the town of Piste and check in at Hotel Casa Novelo (from $20 per night) so we can rise early and arrive before the park opens. Our plan pays off. The next morning, after a five-minute drive we are among the first at the site. Just moments later, the line for tickets snakes through the parking lot.

An iguana perches on the Mayan ruins at El Rey archeological site in Cancun.

The rising sun lights up the Temple of Kukulcan at Chichén Itzá.

Chichén Itzá Enthralls Us

In its heyday, Chichén Itzá was one of the biggest cities in the Mayan empire and served as both a hub for trade and a site with deep spiritual significance. Eager to make the most of our visit, we hire a private guide (about $50), archaeologist Rafael Burgos, a Mayan descendent who grew up in the shadow of the park before it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Temple of Kukulcan, the main pyramid, boasts edges that are impressively straight and razor-sharp, even though the Mayans had only stone tools. The restored 98-foot-tall pyramid is a physical representation of the Mayan calendar. On the spring and summer equinoxes, the late afternoon sun shines on Kukulcan in such a way that the shadows cast by the steps on the northwest balustrade make it appear as though a snake is descending the pyramid.

Each side of Kukulcan, also known as El Castillo, has 91 steps. Multiply that by four sides, one for each season, and add the top, and you have one step for each of the 365 days in a year. On April 6, the sun rises right in the belly of a stone statue of a woman giving birth. At each stop along our roughly two-hour tour, I am more dazzled by the intentionality with which the Mayans lived. Every structure we visit has celestial significance and each intricately carved building, sculpture and place of business also serves as an element of a giant clock.

“Time was the obsession of the Mayans,” Burgos tells us, “time, and the movement of the sun.” They spent years, he says, patiently observing nature and making careful calculations.

Kassondra takes a sightseeing break to relax in Cenote Samula, located in Yucatan.

The steps of the 93-foot-tall Acropolis at Ek Balam

History in Three Dimensions

At the restored ball court, where players competed to shoot a ball through high, narrow stone hoops using only their bodies — no hands — Burgos points out how to tell the time with the shadows cast on the court. The craftmanship of the Mayans was so precise, so intentional, that they even planned the acoustics of their structures. Whispers carry from one end of the ball court to the other. Clap your hands at the base of Kukulcan, and the sound bounces back as the call of a quetzal, a bird the Mayans held sacred.

An hour’s drive west from Chichén Itzá are the ruins at Ek’ Balam. There, we climb the 102-foot Acropolis, which is believed to contain the tomb of an important Mayan ruler. On a clear day, from the top of the temple you can see Kukulcan to the southwest. Look to the southeast, and Ixmoja, the main pyramid at Cobá, comes into view.

The Temple of Kukulcan at Chichén Itzá

Kassondra explores the Nohoch Mul pyramid at the ancient Mayan city of Cobá.

At Cobá, an hour away from Ek’ Balam, on steps rubbed smooth by sneakers and the passage of time, we climb the pyramid as the sky turns golden. At the top, out of breath from the 138-foot climb, I sit and stare out at the land before us as the sun sinks toward the tree line. The absence of other tourists makes it easier to imagine what it may have looked like 1,500 years ago when Cobá was a bustling city and the roads served as busy trade routes.

Earlier that morning, I had tried to conjure an image of the whole ancient world, all its scattered civilizations simultaneously building gravity-defying structures with stunning simplicity. It felt like mental gymnastics — we typically learn history in a much more linear way.

That’s the beauty of renting a car and making a road trip to the past in person. You can see history, rather than watching a documentary or reading a book. Sure, you can learn a lot about the passage of time in two dimensions. But in three, you can feel it.

Decorated plates sit on a table at an open-air market at Chichén Itzá.

Related

Read more stories about Mexico road trips.

- Explore Food, Art and Architecture in Mexico City

- Road Trip to San Miguel Mexico

- Every Hour Is Golden in Mexico’s Loreto

- The Hidden Gems of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula

- Wild Mexico

- Meeting Wildlife Face to Face in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico

- Sinkholes and Underwater Caves Rival Tulum’s Caribbean Beaches

- Tour Mexico’s Río Secreto, an Underground River

- Yucatan Peninsula Beaches

- Weekend Getaway From Mexico City to See Butterflies

- Weekend Getaway to Mexico’s Playa del Carmen

- Todos Santos: A Colorful, Seaside Town in Mexico

- Must-Visit Mayan Ruins Near Cancun