Kenai Fjords National Park

Aialik Glacier is the largest glacier in Aialik Bay, located in Kenai Fjords National Park.

Story and photos by Joe Rogers

Joe is a freelance travel writer and photographer based in Denver, Colorado. See more of his work at The Travelin' Joe or on Instagram.

This remote Alaska destination offers towering glaciers, crystalline waterways and wildlife galore.

The burly, bearded store clerk peers at the can of bear spray on the counter, then at me. “It won’t stop one,” he says.

“Maybe not,” I admit. I know the odds of an attack are one in 2 million, but years of backcountry hiking have taught me to be prepared. “But it’ll distract one.” The clerk shrugs and accepts my money.

I’m in Anchorage, an urban oasis on Cook Inlet and the gateway to Alaskan adventures for most travelers. When I attended college here in 2005, I spent more time outdoors than in class. On this visit, I’ll drive 120 miles to the port town of Seward and then on to explore Kenai Fjords National Park.

The next morning, I steer my rented Ford EcoSport south on Seward Highway. Dense, gray clouds fail to dull the dramatic landscape — Turnagain Arm’s churning surf to my right, Chugach State Park's 3,000-foot peaks to my left. Six miles from Anchorage’s city limits, I stop at Beluga Point, a rocky outpost on the National Register of Historic Places, for the remarkable 180-degree view. From mid-July to August, this is the best roadside vantage point to see beluga whales chasing the salmon run.

At 10:30 a.m., I spot my first bear. A resident at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center in Girdwood, Kuma is comfortably napping high up in a cottonwood. The 200-acre sanctuary at Mile 79 has educated the public about Alaska’s wildlife since 1993. Near Kuma’s expansive enclosure, gray wolves prance in wild grass and reindeer munch on downed leafy branches. All along the center’s 1.5-mile looping trail, excited visitors spy lynx, musk ox, moose, bears, bison and elk.

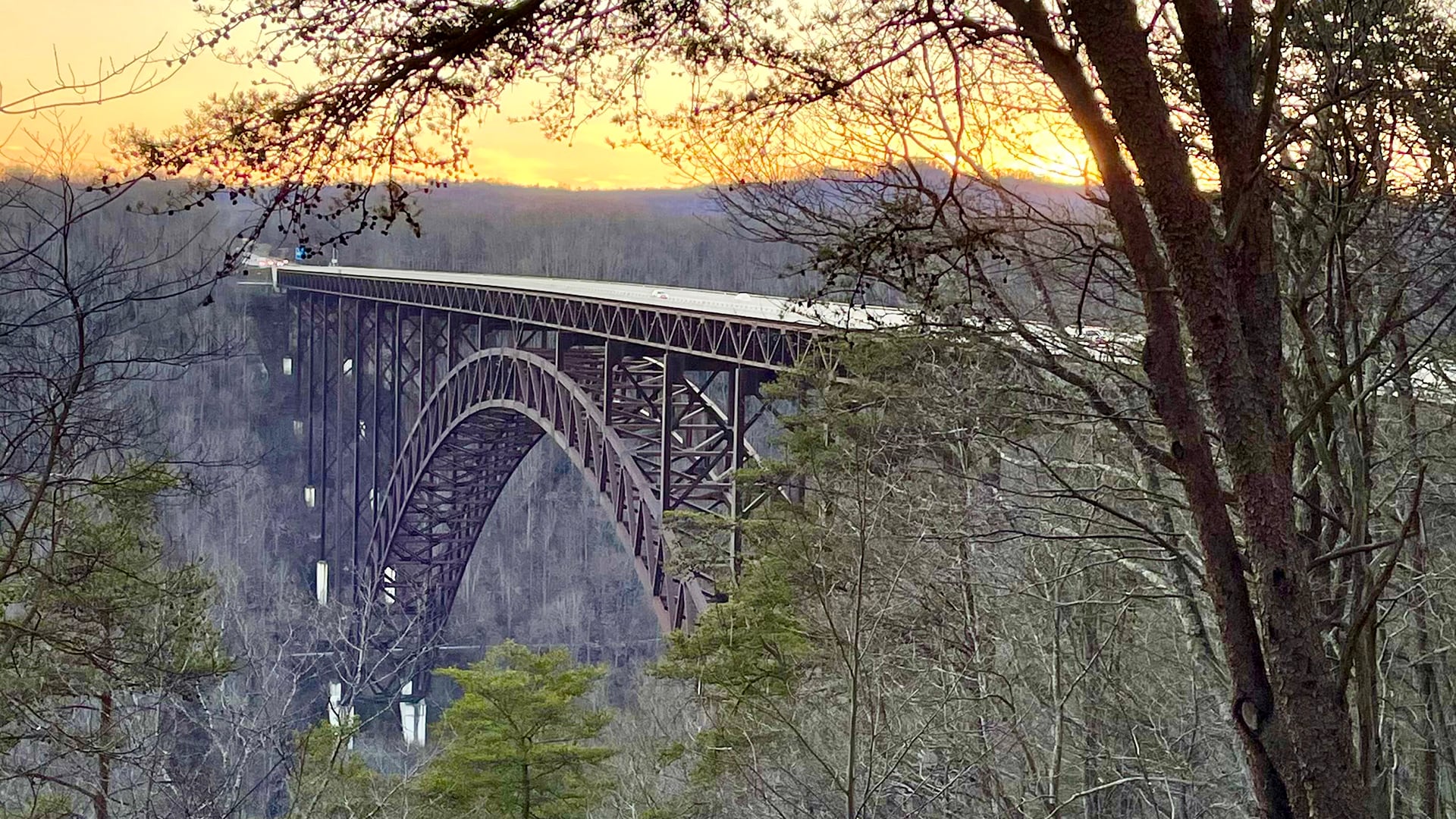

The author enjoys the Canyon Creek Bridge overlook.

Hiking trails to Exit Glacier are just a 15-minute drive from Seward, making it a popular activity in Kenai Fjords National Park.

Park Delivers on Scenic Vistas

Back on the road, just minutes later I see a sign that reads, “Welcome to Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula.” This is “Alaska’s Playground,” and for good reason. The peninsula’s 90% wilderness, delivers world-class fishing and rafting and offers hiking trails and flightseeing tours. The next 80 miles to Seward are a photographer’s dreamscape, with fall foliage decorating wooded valleys and mountainsides, and fishing boats and float planes resting on crystalline lakes.

In Seward, I’m met by a hard, cool rain. From June to August, the town hums with life: cruise ship passengers, paddlers, hikers, mountain bikers and sportfishing enthusiasts. I’m here in mid-September, the tail end of tourist season, when Seward and its harbor are pleasantly still. After a brief stop, I hop in the car and backtrack 4 miles to Herman Leirer Road. Soon enough, the icy giant that is Exit Glacier — estimated to be 23,000 years old — looms in the distance as I make my way to the park’s lone vehicle entrance.

Though much of the park is reachable only by air or boat, Kenai Fjords remains perhaps the most accessible of Alaska’s eight national parks. Much like its counterparts, this expanse of 607,805 acres is a land forged by time and ice, its rocky coasts and glacial bays are the ancestral home of the Sugpiaq people. Wildlife thrives in the icy waters and lush forests, satisfying visitors’ cravings for memorable outdoor adventures.

The rain picks up as I follow the easy, 2.2-mile Glacier Overlook Trail to reach the first of two panoramic vistas at Exit Glacier. Here, the glacier spills down about 3,000 feet from Harding Icefield, a Pleistocene epoch remnant that once covered much of Southcentral Alaska. Awe sweeps over me. A sign marks the glacier’s terminus in 2010, which now is more than 640 yards farther up the valley — a stark reminder of glaciers’ sensitivity to a changing world.

With daylight fading and my stomach rumbling, I return to Seward for dinner at the Flamingo Lounge, a retro-style steakhouse. Local cuisine is part of any good travel experience, so tonight I indulge in halibut chowder and steak to fortify me for tomorrow’s six-hour excursion into the Gulf of Alaska and the national park with Kenai Fjords Tours.

Dirus, a Hudson Bay wolf, lives at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center.

The sun sets on Seward Boat Harbor, bringing as sense of calm after a long day of sightseeing.

A Mile-Wide Glacier, Whales

I’m up before sunrise. Outside, the predawn air is unsympathetically cold and damp. I throw on an extra layer and make my way through town on foot. At the harbor, I’m rewarded with 360-degree views of freshly snow-coated peaks surrounding me on three sides, with the mirror-like Resurrection Bay to the south.

About 11:30 a.m., I board the Callisto Voyager, a 78-foot-long passenger boat. As wet set off, a driving wind pelts my exposed face with stinging rain, yet I relish every minute. From the bow, I watch as Godwin Glacier unfurls below Mount Alice, as we pass coastal rainforests and as Bear Glacier, the park’s largest, spills into the lagoon. Even when surrounded by so much of nature’s brilliance, nothing could have prepared me for Aialik Glacier, which stretches over a mile wide. The size of this lingering ice age behemoth, with its glacial-blue splendor and its bone-chilling breath blowing across the bay, leaves me gasping.

As the tour continues, we see harbor seals, puffins and bald eagles. Steller sea lions nap on rocky shorelines and Dall’s porpoises playfully ride the boat’s bow waves. A humpback whale exhaling plumes of spray in the distance sends everyone portside, hoping for a glimpse of this species that can grow 45 to 50 long and weigh up to 35 tons. Later, a pod of orcas sends us dashing to starboard.

The following morning, I’m kayaking alongside Alex, my Adventure Sixty North guide, as we follow the peninsula’s western coastline to Tonsina Point. It’s too late in the season for the Aialik or Bear glacier tours, but I’m happy to enjoy an easy paddle, soaking up sightings of eagles, Tonsina Creek and the ghost tree forest. The trees died in 1964, when a 9.2 earthquake dropped Tonsina Point about 6 feet, plunging the trees’ roots into salt water.

A kayaker paddles to Tonsina Point during a trip with Adventure Sixty North.

Seward Highway's Canyon Creek Overlook features stunning views of the Kenai Peninsula.

Bear Spray Comes in Handy

Later that afternoon, I’m back at Exit Glacier, attempting a strenuous 8-mile round-trip hike for a view from above. As I start on the Harding Icefield Trail, a pair of hikers stop me to say, “Be careful. We saw three bears at Marmot Meadows.” I thank them for the heads up and tap the can of Counter Assault, ready at my hip.

The trail first meanders underneath a cottonwood canopy, then climbs steeply along a series of switchbacks. Some descending hikers report seeing four bears; others say they saw five. Occasionally, Exit Glacier’s outwash plain and the surrounding landscape come into view, the kind of scenic gifts that are part of Alaska’s appeal.

A third of the way up the trail, I’ve reached Marmot Meadows. I stand still to listen and scan the heavily vegetated slopes above. I see one black bear, well up the slope, minding its own business. I follow a well-worn path leading into a thicket of trees and then down a steep slope.

At a small clearing, the spectacular panorama that is Exit Glacier fully reveals itself. I decide this is as remarkable a place as any to end my adventure. I linger for an hour, sitting quietly with my thoughts. At times like these — with a brilliant sun above, a splendid view and nothing but sounds of the wild — I’m most at peace, comfortably tied to the rhythm of nature and my place in it.

Back in the parking lot, I mention my bear sighting to a young couple starting out on a late afternoon hike to the meadow. When they look hesitant to continue, I hand them my bear spray. “Just in case,” I say, smiling. “The view is worth it.”

Sorbus sitchensis grows along the Harding Icefield Trail. The fruit provides food for grizzlies and black bears.

Related

Read more stories about outdoor adventure.

- DELETE - Road Trip on the Berkshire Cheese Trail

- DELETE - Weekend Getaway to Grand Lake, Colorado

- DELETE - Weekend Getaway to Catskill Mountains, New York

- Cumberland Connection

- DELETE - Llama Trekking in New Mexico

- Road Trip to See Whales

- Road Trip to Colorado Mountains Fourteeners

- Grand Canyon Hike

- Glamping in Oregon

- Coquihalla Mountain Skiing

- Old Friends Drive the Sea to Sky Highway

- Floating on Ozark Rivers

- Crater of Diamonds

- Caving in the Black Hills of South Dakota

- Great Smoky Mountains Waterfalls

- Washington's San Juan Islands

- Road Trip to Saguaro National Park

- An American Safari

- Road Trips to See Wildlife

- Kenai Fjords National Park

- Every Hour Is Golden in Mexico’s Loreto

- Road Trip to Red Rock Canyon Near Las Vegas

- New River Gorge National Park

- Road Trip for Florida Fishing

- Weekend Getaway to Tofino, Canada

- Day Trips From Las Vegas

- Hot Air Ballooning in Arizona

- Road Trip to Hikes along the Crooked Road

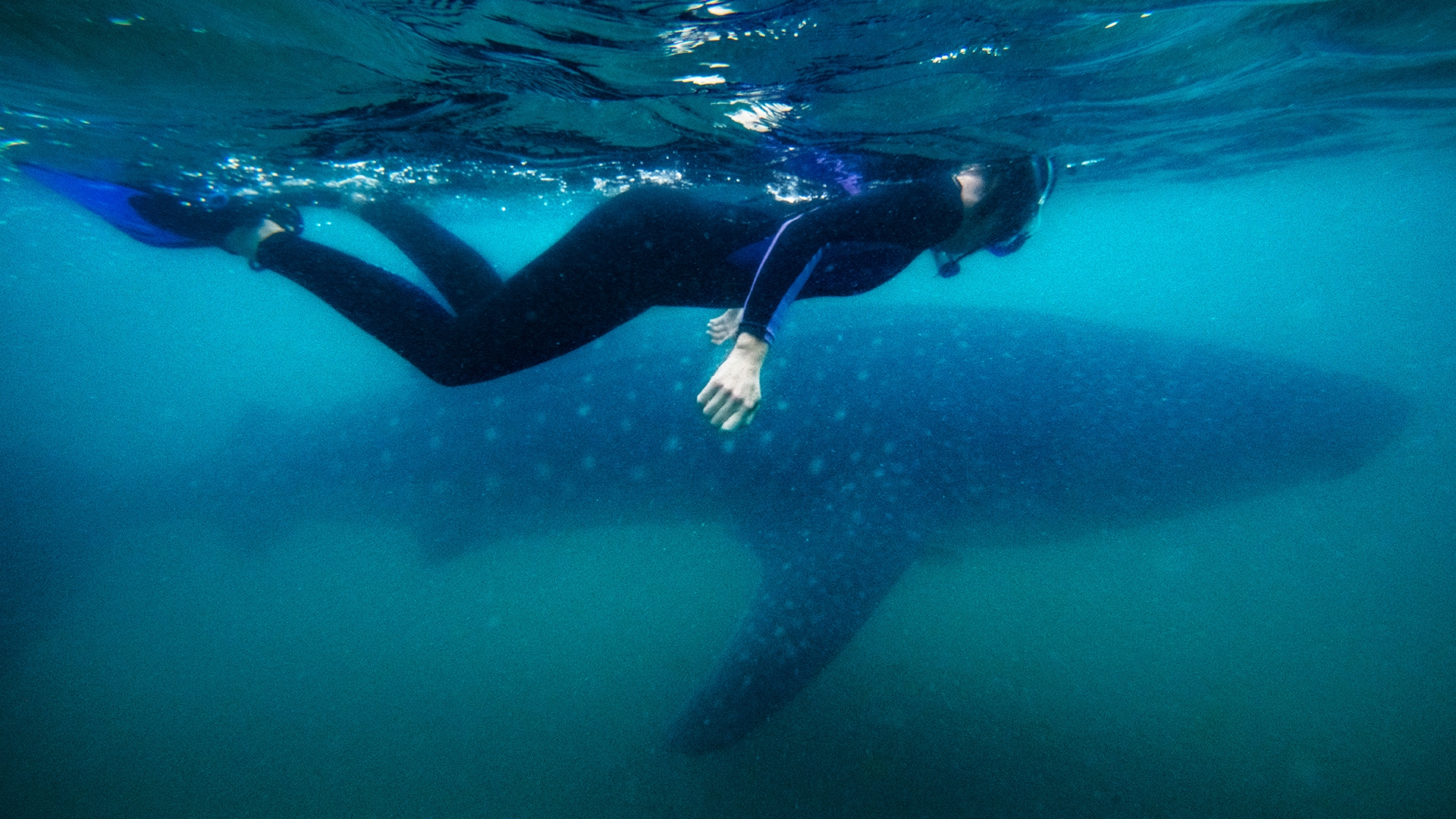

- Meeting Wildlife Face to Face in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico

- Road Trip to Canyon de Chelly National Monument

- Road Trip to Colorado Mountains Fourteeners Attractions

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- Sinkholes and Underwater Caves Rival Tulum’s Caribbean Beaches

- Weekend Getaway to Palo Duro Canyon, Texas

- Southern Illinois Road Trip Features Hidden Gem Outdoor Adventures

- Road Trip to Snowy Range Scenic Byway

- Algonquin Park Scenic Drive

- Tour Mexico’s Río Secreto, an Underground River

- Road Trip to Wyoming's Flaming Gorge

- Hunting for Wild Mushrooms in Indiana

- Road Trip to Nova Scotia's Wild Berry Bounty

- Nature Photography Tips

- Glamping in the Catskill and Adirondack Mountains

- Stargazing in Texas: McDonald Observatory and Beyond

- Mountaineering in the Canadian Rockies

- Romantic Getaway in Sedona, Arizona

- Road Trip on Maine's Pequawket Scenic Byway

- Road Trip to Whale Watch Spots

- Isle Royale National Park

- Weekend Getaway From Mexico City to See Butterflies

- Visiting Washington's Olympic National Park in the Offseason

- South Dakota Black Hills

- Icefields Parkway 3-Day Driving Trip

- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness

- Todos Santos: A Colorful, Seaside Town in Mexico

- Weekend Getaway to San Luis Obispo

- Vancouver Spawns New Friendship

- Road Trip to Montana’s Independently Owned Ski Areas

- Must-Visit Mayan Ruins Near Cancun