Alex's Astronaut Dream

Above photo: Alex holds rockets that take weeks to plan, engineer and assemble.

Story by Jesse Hirsch; photos by Neill Whitlock

Jesse lives in Brooklyn, where he writes about food, agriculture and travel. Neill lives in Dallas. See more of his work on his website.

For this high school student, the decision to cast away childish things came early.

While other kids asked for the latest trendy toys each Christmas, she was begging her parents for chemistry sets and crystal-growing kits. "I was this total nerd," she says with a grin. "I was totally OK with everything revolving around science, and my parents supported that."

Given her early leanings, it's no huge surprise where Alex ended up: she's a bona fide rocket enthusiast, her enthusiasm only matched by her level of talent. Ever since she entered middle school and joined the after-school engineering program — supplemented by daytime engineering classes — Alex has been driven by an overarching passion for rocketry.

Before that, her curiosity had turned skyward; she did a massive science project analyzing the benefits of growing mushrooms in space. Ask Alex about that project, and you'll get a sense of her scientific rigor: "[The project] was about nutrition and how we can adequately feed astronauts without bone deterioration and muscle atrophy," she says. "So I did research, and I implemented a project, and basically created a self-sustaining ecosystem that could survive in space." Not too shabby for a kid who was years from even driving a car.

Alex is a shining example of the gains that can be achieved from prioritizing STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) at an early age. She was lucky enough to grow up with STEM professional parents (nursing and information technology) who actively nurtured her passions early on. They would shuttle her around to extracurricular activities and never complained, even when the volume of events accelerated in high school. And when she was younger, collecting and cataloging rocks as a pastime, there was never any of the horror stories you hear from some households, a la: "Honey that's inappropriate. Wouldn't you rather play with dolls?"

A wealth of research has shown how invaluable this home support can be for encouraging kids to follow their dreams — especially with STEM. Alex was also lucky enough to grow up in a school district (McKinney, Texas) that allots a generous amount of resources to STEM education. On top of the official curriculum, she has been able to benefit greatly from building rockets after school. Additionally, the Dallas Area Rocket Society (DARS) provides a wealth of resources for budding rocketeers, from knowledge to equipment to launch space.

Alex assembles a rocket at her high school's lab.

Alex dreams that one day she’ll be able to go to Mars — and send her mom a selfie.

At Alex's after-school rocketeering club, led by engineering teacher Robert Gupton, she gets the chance to build working rockets from conception to completion. "This is not a kit," says Gupton, referring to the common model rocket sets available at hobby stores. "They are basically creating [the rockets] from scratch." This includes everything from preliminary design review to intensive 3-D modeling to cutting parts using a high-precision laser cutter.

It's also a highly competitive group; McKinney teams advanced to the national Team America Rocketry Challenge two years in a row (only 100 teams make it each year), even managing to snag second prize. This led to the incredible honor of building a rocket for NASA, an intensive, yearlong process that involved periodic NASA conference calls, PowerPoint presentations and loads of planning. "The students ended up doing everything an engineer would do!" boasts Gupton.

Alex cites this NASA experience as likely her life's proudest achievement (though there are surely many more to come). She was the youngest member of her team, a distinction that suffuses her with a well-earned sense of pride. Additionally, she was one of the only females in the club when she first joined — they now have an all-girl team in addition to two others — which gave her an added sense of something to prove.

Alex and her dad load rockets into a pickup truck.

Success! Alex’s model rocket ignites and leaves the launch pad.

"I was kind of intimidated at first," she says, "just because, you know, here I am as this little freshman and I’m in a room full of guys. And then I kept getting comments like, 'Oh, you get special advantages because you’re a girl.'" Alex fought hard to resist this misconception, saying she worked "twice as hard" to prove that she was every bit as smart and competent as her older male peers. And now that she's an upperclassman, it would seem she has earned their respect.

There is still a lot of work to be done in society at large, encouraging young women to pursue their interests in STEM and resist all the naysayers. Alex says she still sees mostly guys at DARS launches, brought there by their dads and granddads. Nonetheless, she's an optimist. Alex sees things evolving as time progresses, and bears hope that future generations of scientists will achieve more equality.

"It’s a good field for both genders, because there isn’t necessarily a right way to get something done," she says. "You just have to get something done that’s correct or factual. That's science."

DARS members and local Cub Scouts watch Alex’s rocket take off.

Related Articles

- Alex's Astronaut Dream

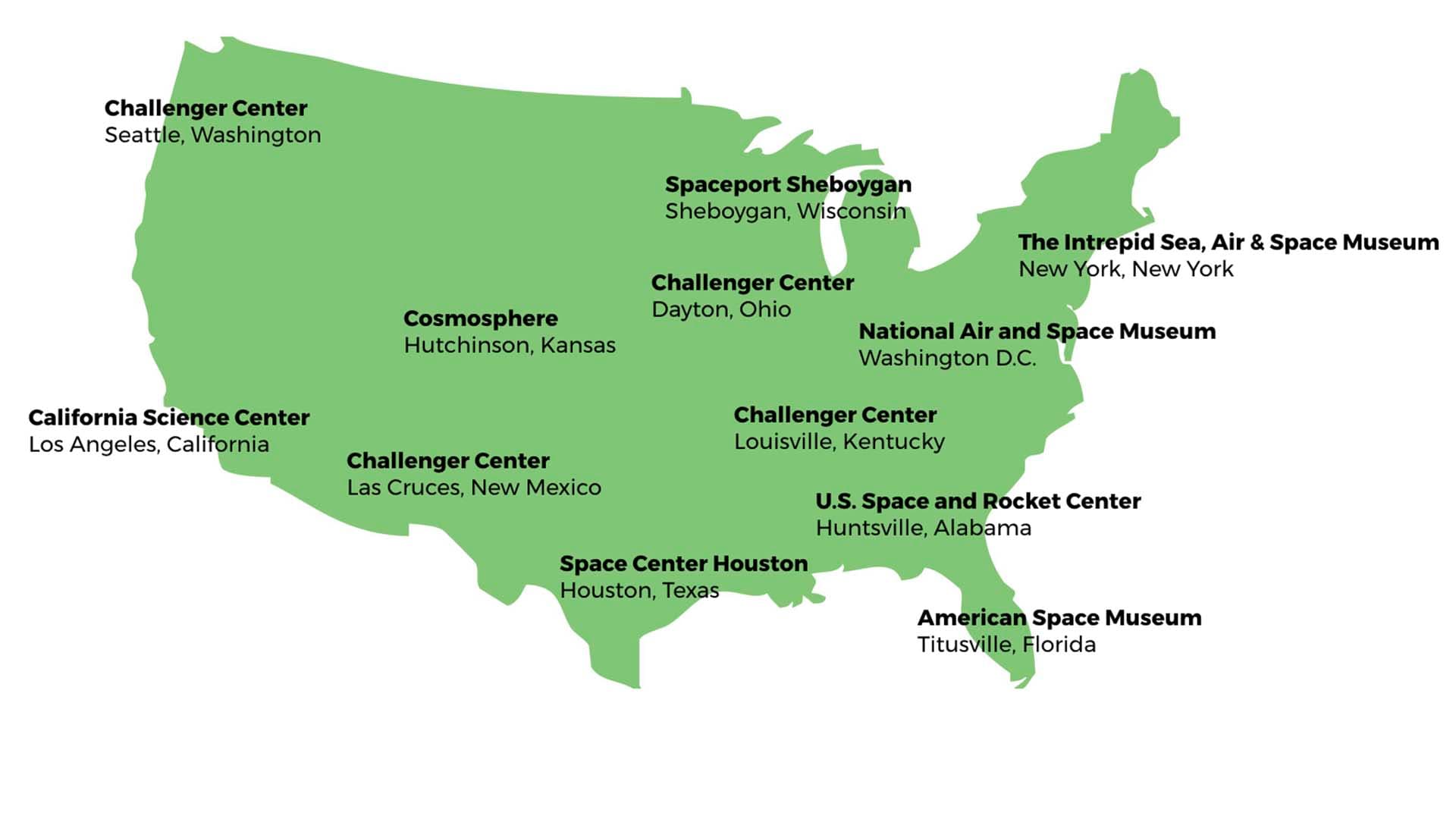

- Rocket Road Trips

- DELETE - Rocket People of Texas